Part 1 of this three-part blog series focused on Radio Shack’s origins and how a savvy businessman named Charles Tandy began to transform a chain of bankrupt Boston radio stores into America’s one-stop shop for consumer electronics. By identifying his ideal customer (the hobbyist) and offering to the market an authentic value proposition, Tandy laid a foundation that would open the door for decades of prosperity and growth.

Here in part two, we’ll look at how strengthening one key element of Radio Shack’s value proposition transformed the company from an emerging electronics chain into an American retail juggernaut.

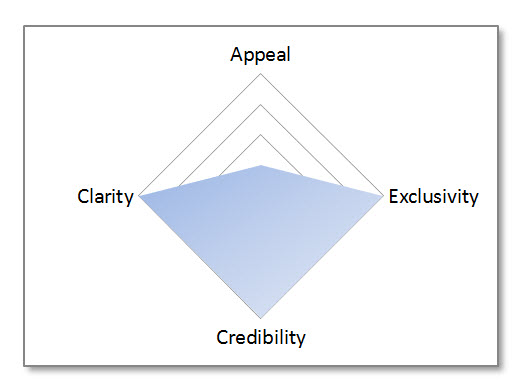

The four elements of a strong value proposition

Though the “value proposition” we modern marketers speak of has gone by numerous names over the years — unique selling proposition, basic selling proposition, strategic differentiation, etc. — one underlying principal has remained largely the same:

The most successful value propositions boast credibility, clarity, exclusivity and appeal.

As the 1970s began, Radio Shack had their specific market cornered in three of these four key elements. The chain was widely regarded as having the most knowledgeable sales staff in retail. (Credibility — Can I trust your claims?)

Radio Shack’s meticulous mass and targeted marketing campaigns clearly communicated the specific goods sold within stores. (Clarity — What are you actually offering?)

Each store’s unique inventory of specialty parts and equipment gave Radio Shack a near-monopoly on the hobbyist market. (Exclusivity — I can only get this from you)

The only area where Radio Shack lagged behind was appeal. (How much do I desire this offer?) Though small, high-margin, house-brand items drove the majority of the company’s sales, batteries, capacitors and wire weren’t exactly the type of glamorous items that lured in window shoppers.

Early 1970s Radio Shack Value Proposition Lacked Appeal

Staying on the forefront of innovation

An exclusive offer without appeal has its force undermined by a lack of attraction.

— Flint McGlaughlin, Managing Director and CEO, MECLABS Institute

While selling exclusive, highly-specific parts and accessories to its target customers kept Radio Shack’s margins and gross profits high, CEO Charles Tandy decided to also position the chain as the leading seller of cutting edge consumer technology. The newest innovations in home audio equipment, gadgetry, robotics and productivity devices, such as personal calculators — which drew a broader interest while still resonating strongly with Radio Shack’s target customer — could all be found and tested at the neighborhood Radio Shack.

Though the profit margins weren’t nearly as high on these items, they added to the appeal of the in-store experience and turned Radio Shack into a genuine electronics showroom worth going out of your way to visit. This authentic combination of exclusivity and appeal made Radio Shack a can’t-miss destination.

Radio Shack’s first big hit

One item in particular caused Radio Shack’s business to soar in the early 1970s: the CB radio. Though the Citizens’ Band radio service was launched decades earlier by the FCC, equipment was heavy, expensive and served only niche purposes.

Then came America’s 1973 oil crisis. Fuel shortages were rampant, and the U.S. government responded by rationing gasoline and imposing a nationwide speed limit of 55 miles an hour. The use of CB radios exploded during this time, first by truckers and then by amateur enthusiasts.

Truckers, who were often paid by the mile, were hit particularly hard by the oil crisis and would use CB radios to share information about speed traps with fellow truckers. Truckers and amateur radio enthusiasts alike also used CB radios to swap tips about which gas stations had fuel in supply.

By honoring and harnessing its core value proposition — “(Because) Radio Shack stores provide specialized, innovative parts and merchandise not available anywhere else, sold by the most tech-knowledgeable staff in retail” — Radio Shack rode the CB wave to staggering success, not only selling the widest variety of exclusive CB radios in the world, but providing customers with the assistance and training necessary to operate them.

At the height of the CB craze, Radio Shack produced 16 different models, all significantly lighter and cheaper than those sold in the past. For several years, these radios accounted for nearly 30% Radio Shack’s business.

Radio Shack CB Radio Commercial (1976)

Entering the PC market

Radio Shack Enters the PC Market

As the U.S. emerged from the oil crisis, sales of CB radios declined sharply.

Fortunately, Radio Shack was poised to be on the forefront of the next major technological boom — personal computers. The PC market was only in its infancy at the time, but Charles Tandy recognized a potential goldmine for Radio Shack in this emerging product category.

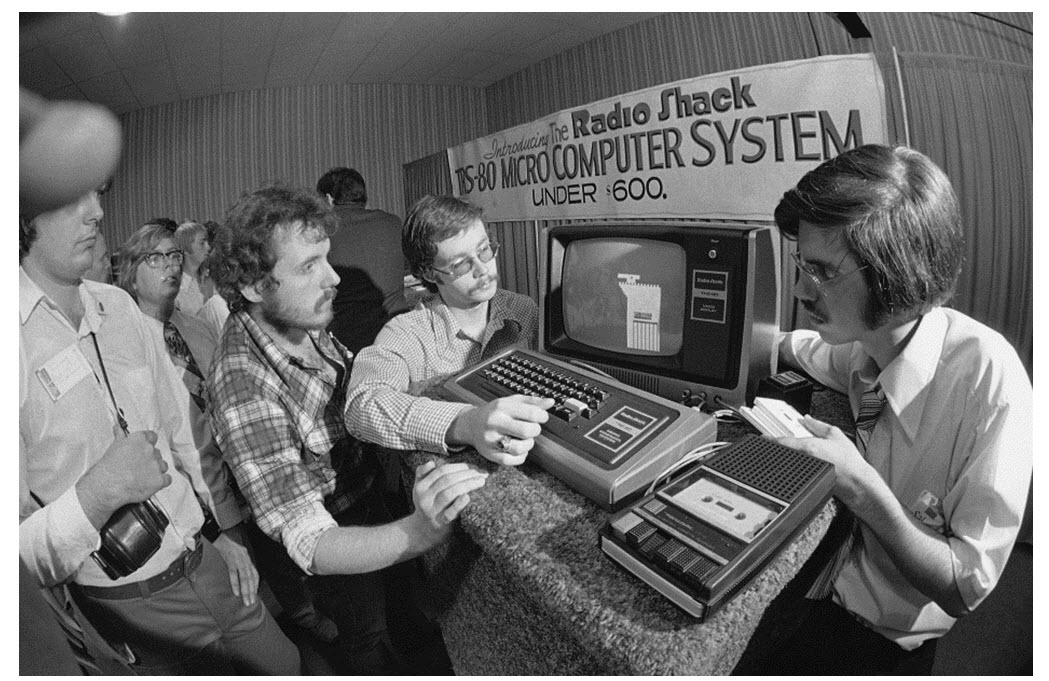

Though Radio Shack was already a one-stop shop for computer enthusiasts looking to build their own computers, Tandy (with coercion from manager of Tandy Data Processing, John Roach) prepared to take the biggest risk in company history. Radio Shack would design and sell its own preassembled personal computer — the Tandy TRS-80.

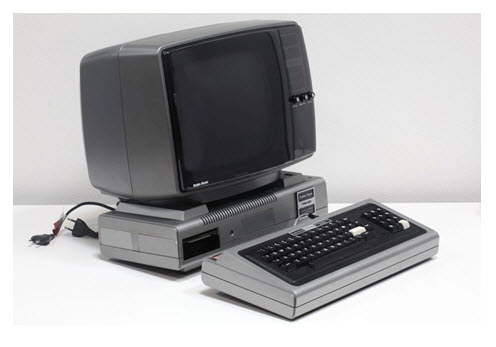

While previous computers had filled entire rooms, the TRS-80 fit neatly on a desk. It included a full-stroke QWERTY keyboard, a black and white monitor and a data cassette recorder for storage.

Tandy TRS-80 Computer

Charles Tandy was decidedly risk-averse, and because of this, he only commissioned an initial run of 1,000 TRS-80 computers. Even this bet was hedged. The $600 machines ($2,300 in 2015 USD) were the most expensive item Radio Shack had ever sold, and if they didn’t sell through, he planned to write the computers off and use them for in-store inventory management.

When the TRS-80 was officially unveiled at the Personal Computer Faire in Boston in 1977, the Associated Press ran a front-page article, marveling about how a consumer-electronics company could create a device that could “do a payroll for up to 15 people in a small business, teach children mathematics, store your favorite recipes or keep track of an investment portfolio, and also play cards.”

Following publication of the story, over 15,000 people called to purchase a TRS-80 — shutting down Radio Shack’s switchboard — and a quarter of a million people joined the waiting list by putting down a $100 deposit.

Radio Shack Tandy-1000 (a later TRS-80 color model) Commercial

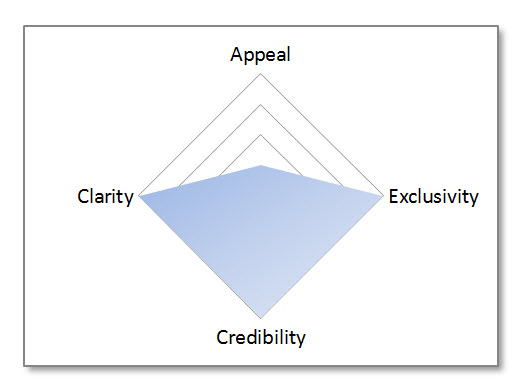

The TRS-80 was a massive early success. The computers disappeared from store shelves as quickly as Tandy could produce them, easily outselling rival computers from Apple and IBM. Despite the CB radio market drying up, Radio Shack remained comfortably in the black, as nearly 100,000 TRS-80s were sold while hobbyists continued to buy high-margin private label items in droves.

This early success of the TRS-80 represents Radio Shack’s absolute peak as a company.

Radio Shack was firing on all cylinders by super-serving hobbyists, selling the newest in technology to early adopters and providing award-winning customer service that made Radio Shack one of the most trusted brands in America.

By keeping a laser-sharp focus on its authentic value proposition, Radio Shack’s ideal customer truly did view the company as “Best in America” during this time period:

Radio Shack “Best in America” Commercial

Radio Shack begins its decline

On Nov. 4, 1978, Charles Tandy died suddenly in his sleep. He was 60 years old. Tandy’s unexpected passing created a massive vacuum within Radio Shack. Despite the company’ssize — Radio Shack now had more retail locations than McDonalds — the company was very much the product of Tandy’s singular vision and marketing philosophy. There was concern from investors that without Tandy’s direction and work ethic, the company might lose its way.

It took only five years for that concern to be realized.

Looking forward

Parts one and two have documented one company’s meteoric rise due to offering to the market a unique, authentic value proposition built upon a foundation of exclusivity, appeal, credibility and clarity.

As marketers, these four key elements dictate the strength of our value props.

No matter the external temptation, we should continuously strive to refine, rather than dilute, the comparative strengths of our exclusivity, appeal, credibility and clarity. For, as we noted in part one, the specific offer to the specific person will always outperform the general offer to the general person.

In Part three, we’ll take a look at what happened when Radio Shack began trying to be all things to all people, greatly diluting a once-bulletproof value proposition.

You can follow Ken Bowen, Manager of Partner Content, MECLABS Institute, on Twitter at @KenBowenJax.

You might also like

Value Prop: How Radio Shack lost its way by losing sight of its ideal customer, Pt. 1 [More from the blogs]

Value Proposition: NFL’s Jaguars increase revenue with customer-centric marketing [More from the blogs]

Testing and Optimization: How to get that “ultimate lift” [More from the blogs]

Thanks Ken for such a interesting post.

Thanks Kumar! Much appreciated.