Direct from the Source: What a value proposition is, what it isn’t and the 5 questions it must answer

Michael Lanning invented the term “value proposition” back in the 80s. Since then, it has become a staple in the marketing lexicon, and volumes have been written on the subject, including Lanning’s own book, Delivering Profitable Value: A Revolutionary Framework to Accelerate Growth, Generate Wealth, and Rediscover the Heart of Business.

I had the privilege of speaking with him recently about how the concept has evolved over the past three decades and what he thought about that evolution.

“‘Value proposition’ has been widely adopted since the 1990s as a marketing and selling tool — everyone knows they need a good value proposition to sell their product,’” Michael said.

However, Michael believes the focus is too narrow and misses the opportunity to influence business strategy. Michael explained that value propositions should:

1. Drive, but not be equated with, your message. It should be an internal articulation, to be echoed by your message. It should not be your actual selling line or slogan.

2. Focus on the specific, measurable experiences customers will derive by doing business with you.

“Contrary to how things may seem, customers don’t really care about your product. They care about their lives or businesses; they care about what they may or may not get out of using your products or services,’” Michael said. “So what matters and what must be at the heart of a real value proposition is those customers’ resulting experiences that happen because they buy [or] use your stuff rather than some other option.”

3. Be reflected across and influence your entire business — not just your messaging, marketing and sales.

“It should be the fundamental choice, creatively discovered, then debated, articulated and agreed internally by leadership across your entire business,” Michael said. “It should fundamentally determine the very business you are in, which customers you seek and what your business will do to improve their experiences in return for their business.”

Lanning believes marketers often write reasonably defensible value propositions in the sense of telling people why they should buy a product or at least implying what they’ll experience. But these marketers’ organizations don’t necessarily go through the rigorous process of deciding internally what those experiences will be or how they will happen.

“You do have to communicate to customers, giving them a strong reason to use your offerings, but you also need to ensure the customer will get the results thus promised,” Michael said.

Michael acknowledged that it is a major challenge to integrate an entire business around delivering — both providing and communicating — a value proposition. However, for this discussion, the focus was on what a value proposition should include.

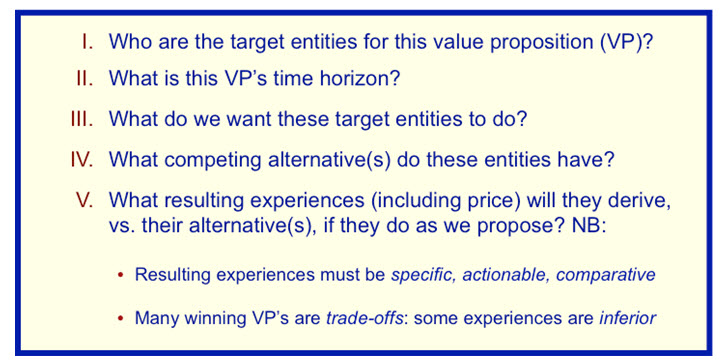

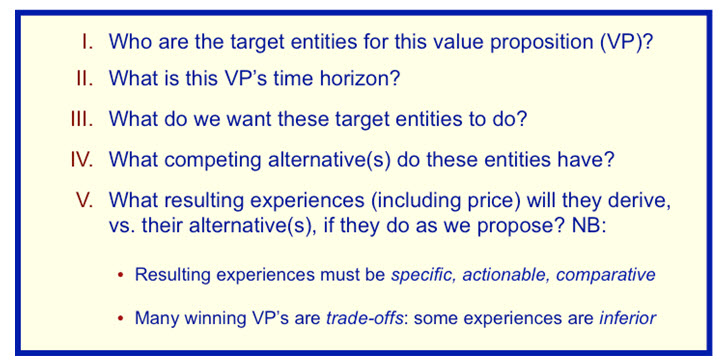

He believes a real value proposition is a strategic document that expresses the purpose for your business. It thoroughly answers five questions:

1. Who are the target customers?

What are their demographics, current product and service usage and other key behaviors? What situation makes them your target?

2. What is the timeframe?

“If you write a vague enough value proposition, it will be good in 2015 and 2050 and anytime in between,” said Michael. “But that just means you’re being vague.”

In reaction to new competitors, technology or regulation, it may be necessary to eventually revise the value proposition.

“Write a specific value proposition for the current timeframe and another for the future, or at least indicate that one will need to be developed,” he advised.

3. What do you want these target customers to do?

- Buy your product or service?

- Use your product or service in a particular way?

- Sell your product or service to their customer?

- Use it to make another product, etc.?

Be clear on what you want the customer to do. This might include adopting new behaviors and experiences, changing business processes or how they manufacture in major ways.

4. What are their competing alternatives?

What action could these customers take if they are not doing what you want? This could be using your direct competitor’s product or maintaining the status quo.

5. What resulting experiences will customers derive by doing what you want, compared to their alternatives? This includes price and any costs and tradeoffs they must accept.

Here you must decide what impact, in net, your business will have on your customers’ lives or businesses compared to their competing alternatives:

- If B2B, how will their business be improved? Will they increase sales? Reduce cycle times? Cut operating costs?

- If B2C, how will some aspect of their life improve? Will they have more fun, save money, be better entertained, save time or improve their health?

- What do you believe is the value of these experiences, compared to the alternatives?

“If you’re not clear on how the customer is better off and to what extent, you aren’t even close to having a value proposition,” Michael said.

This requires diving deep into specifics. For example, a company with a product meant to reduce cycle time would ask questions such as:

- By what measure does it reduce cycle time?

- How much more time will this reduce than the competition?

- Are you comparing it to the status quo, or are you reducing it against three other solutions that are quite different?

Will the customer’s experiences improve enough so that they’ll pay the price you’re asking and accept any tradeoff? The hard truth is that few value propositions beat the competition on everything.

Most winning value propositions include some tradeoff where using your product delivers one or more experiences that fall short of the competition. These tradeoffs need to be included in the value proposition, regardless of whether you communicate them to customers.

“You need to understand and, at least internally, recognize any tradeoffs. The customer will have to accept those tradeoffs and experience what’s inferior. That’s a part of the value proposition,” Michael said. “And net of the tradeoff — that inferior experience — you have to ask, ‘Does the customer still get superior value from us?’”

He provided an illustration: “An expensive sports car may be notoriously unreliable but popular anyway because of its beauty and speed. The value proposition is a tradeoff, but, for the target customer, it’s superior in net.”

In essence, what in your product and all other aspects of your business going to make happen, in the life of your customer, so that they’ll buy into your offer, including the price you’re asking?

“A strong value proposition makes you think through what the customer gets and will conclude at the end of the day,” Michael said. “It is a strategic decision, and among all functions in the business, there must be consensus around it.”

Here’s a summary of the five key questions for a real value proposition:

You can follow Brian Carroll, Executive Director, Revenue Optimization, MECLABS Institute, on Twitter @brianjcarroll.

You might also like

4 Perspectives That Should Shape Your View of Value Propositions [More from the blogs]

Michael J. Lanning’s Academic Lecture Series [From MECLABS.com]

Powerful Value Propositions [MarketingExperiments resource]

Value Proposition: 4 questions every marketer should ask about value prop [More from the blogs]